By Robert Soto, Aug 2014

Well, it has been an interesting seven and half year journey. Most of you have no clue as to why we filed the law suit. It started on March 11, 2006 when agents from the Department of Interior of the Fish and Game Department went to our powwow dressed as tourists and filmed and photographed all the dancers at the pow wow. A couple of hours later, an agent from the department came and invaded what we call a sacred gathering, our pow wow. The circle is a special place we not only dance, but it is a place of prayer, a place of ceremonies, a place of traditions and a place where we can just express ourselves as Native People.

While at the pow wow, I went to a booth outside the gym in the hall way and I noticed a man harassing my brother-in-law. As I got closer, he waved his badge and told me he was an agent of the Department of Interior, Fish and Game. Then he said to give him my two eagle feathers that I was wearing on my porcupine roach. The feathers that my brother-in-law had were mine. Before I knew it the federal agent tried to enter our circle in the gym. I stood in front of him to block him from going in. What happened next was the craziest excuse for violation of our circle that I had ever heard.

He said he had the right to enter into the circle because we had violated three federal laws that ceased the sacredness of the circle giving the United States Government the right to enter our circle and harass our dancers. He stated the laws we violated in the form of three questions. He looked at me and said, "Are you a member of a Federally recognized Tribe. I said I was not so he said, "The law states that if you are not a member of a Federally reconized tribe, this is a violation of Federal Law and the circle ceases to be sacred." Then he said, "Did you advertise the event in the newspaper?" as he waved a copy of the article we wrote with a picture and an invitation for the public to attend the pow wow. I said, "Yes." He then said, "Federal laws says that when a Native American advertises his event in the newspaper, the event ceases to be sacred giving us the right to come and do as we please." Then he said, "Was there the exchange of money in the circle, like a raffle, fifty/fifty, cake walks, vendor's selling their crafts and did you honor a veteran by putting a dollar at his feet?" I said, "Yes." Then he said, "Federal law states that if there is the exchange of money in the circle, the circle ceases to be sacred thus giving us the right to come in and do as we please."

While he went to his truck to take away the beautiful traditional bustle my brother-in-law had made, I went in and warned all the Native people in the circle who had eagle feathers that the Feds would soon be in the circle and I would not be able to hold them back. All I could think about was Custer and the 7th Cavalry sneaking in and massacring our Native people all over again. The enemy came and struck our pow wow when we least expected.

An event made to celebrate and enjoy turned to chaos as our children ran with fear in their faces seeking their parents' protection from the Federal Government who, through their unjust laws, had violated a place that had always been sacred to our people, the Circle. What would happen tomorrow if our churches or our civil organizations were closed because they advertised their service in the newspaper or because they took up an offering? I am writing this so that you can understand why I had to start this journey almost eight years ago and why I decided that I would fight this until the day I take my last breath.

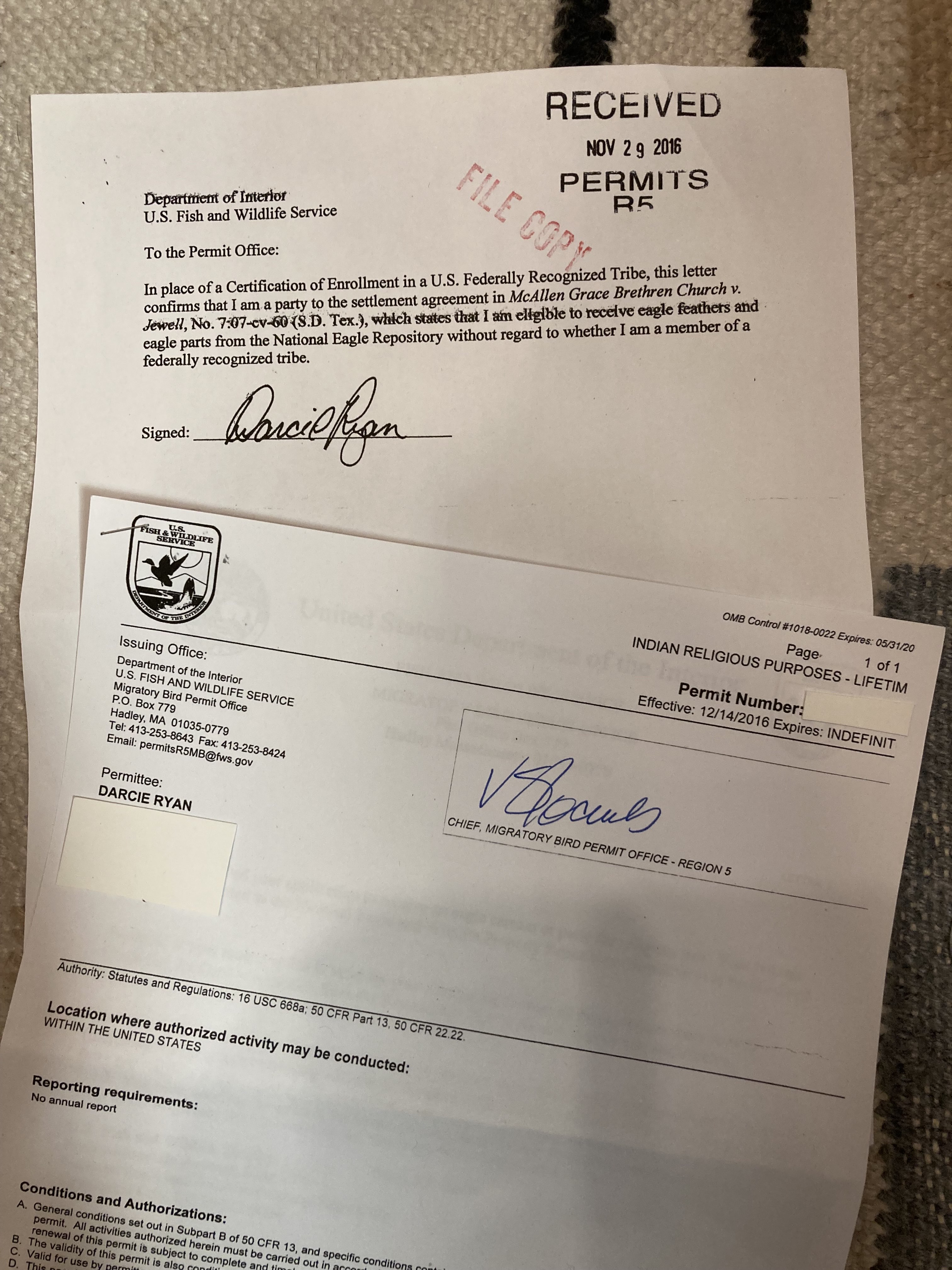

For background of nine years of litigation on the rights of Lipan Apache to use and possess eagle feathers for their American Indian religious and ceremonial practices, read "Factual and Procedural Background" in McAllen Grace Brethren Church et al v Salizar and "Recital" in McAllen Grace Brethren Church et al v Jewell (see links below).

In August 2014, after nine years of litigation by Robert Soto and plaintiffs, the Fifth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, a Federal Court of Claims, found that the seizure of 50 (originally reported as 42) eagle feathers in the 2006 pow wow violated Robert Soto's rights as a "sincere adherent to an American Indian religion" under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993. They concluded that Congress did not specifically aim to safeguard the religious rights solely of federally recognized tribe members.

In the case of Soto, the Court accepted that he was "without dispute an [American] Indian" and a member of the Lipan Apache Tribe acknowledged to have "long historical roots" in Texas and who had a history of "government-to-government" relationships with the Republic of Texas, State of Texas, and the United States. The opinion discussed and was limited only to "Soto's RFRA claim based on his and his tribe's status". They remanded to the lower district court for proceedings consistent with their opinion, and the case was cabined to "Native American co-religionists" (referring to the "religious practices of real Native Americans").

On March 2015, the Department of Interior returned the 50 eagle feathers taken at the 2006 pow wow to Robert Soto. Some of the plaintiffs in the case joined Soto at the cleansing ceremony as the federal agent returned the feathers.

Although the feathers were returned and even if used in American Indian religious practices, the law criminalizing feather possession by individuals who were not enrolled in federally recognized tribes had not been repealed by the federal government. Therefore, the "American Indian plaintiffs" filed a motion for injunctive relief, seeking to prevent the government from "investigating or punishing" them for their religious practices while the case [was] pending". (The Plaintiffs' Motion for Entry of Preliminary Injunction, McAllen Grace Brethren Church v. Jewell, No. 7:07-cv-60)

After the Motion for injunctive relief was filed, the Department of Interior requested a settlement to the case. And, on June 3, 2016, the DOI and the plaintiffs signed a settlement agreement whereby the Department of Interior granted lifetime permits to over 400 Native Americans plaintiffs who were not members of federally recognized tribes to "possess, carry, use, wear, give, loan, or exchange among other Indians, without compensation, all federally protected birds, as well as their parts or feathers" for their "Indian religious use", in accordance to "the terms set forth in the DOI's February 5, 1975 'Morton Policy'". The case was officially closed on February 17, 2017.

Federal Court Cases: