By N. M. Minor (Edited by H. Walking Woman), Nov 2009

The U.S. military records of the era only tell a small portion of the story of the attempted destruction of the Lipan Apaches. It is easy to forget the suffering of the Lipan people when reading telegrams breathless with the details of a "hot pursuit" chase. The story of Kesetta and Jack reveals the personal suffering endured by Lipan families who were targeted, month after month, by troop commanders who had, just a decade earlier, fought in some of the bloodiest battles of the American Civil War and brought the same scorched earth tactics to bear against the Lipan Apaches. During these years, the Lipan people endured more than any people should have to endure.

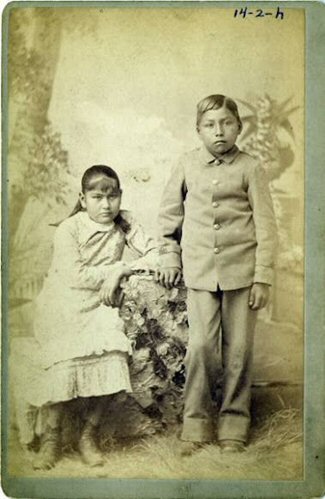

Kesetta, a young Lipan girl about ten years old, and a young boy, Jack, a few years younger, were taken prisoner by a 4th Calvalry soldier during the June 1877 attack on a Lipan camp near Zaragosa in which nineteen Lipans were killed.1 Kasetta and Jack were later considered siblings but this is not truly known; it is also possible they were just two cousins or even unrelated children from the same camp. They were brought back to Fort Clark and "adopted" by Charlie Smith and his wife, Mollie. Smith was a member of the regimental band and was stationed at Forts Clark and Duncan from 1877 to 1880. In 1880, he and his wife were posted to Fort Hays, Kansas. In March 1880, the Smiths turned over the children to the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania as Kesetta Lipan and Jack Lipan and were classified as "prisoners." The children's last names were soon changed to Kesetta Roosevelt and Jack Mathers.

"When Kesetta was given a full medical examination upon her arrival at the school, the staff discovered three large scars—one on her forehead and two on the front and back of her shoulder. When questioned, Kesetta reportedly told them they were left from wonunds inflicted by a stone her mother had used to try to kill her, 'so as to keep the white men from getting me in the fight.'" (Fear-Segal, 207, pp. 255-260)

Jack Mathers died young of tuberculosis in 1888 and was buried at the school's cemetery under the name of Senaca student Jack Martha, but Kesetta continued to live at the Carlisle School or be associated with them until her death in 1906 at age thirty-nine, earning the sad distinction as the longest-enrolled student. In 1906, she had an "illegitimate" son name Richard who was fathered by an unknown white man when Kesetta was lent out to work at a local home, the Bishops. Kasetta died in 1909 and Richard's Lipan heritage was never revealed to him. Orphaned, forcibly removed from her Lipan family, taken as a prisoner of war, forcibly acculturated into the Anglo world, and ostracized by the Carlisle School for her pregnancy, Kesetta’s past was erased (Fear-Segal, 2007, p. 260; Gilfillan, personal communication, August 18, 2018). Both Jack and Kasetta died still classified as "prisoners" at the Carlisle School.

Kesetta and Jack's story symbolizes the plight of the Lipan people after 1850. Afraid to publicly acknowledge their tribal affiliation, they blended like chameleons into the surrounding society. Even Lipans who were forced onto reservations could not officially celebrate their heritage nor openly practice their traditional culture. They were "guests" of the Mescaleros, Tonkawas, and Kiowa Apaches. For that portion of the tribe who did not enter a reservation and thereby escaped death at the hands of U.S. troops, could no longer represent themselves as "Lipan" to the outside world, for to do so might reactivate old arrest warrants or spark the interest of a bounty hunter looking to make $50 for a Lipan scalp (Ord, 1877; Turner, 1877). The non-reservation remnant passed into the Tejano world of south Texas and among the Hispanics of northern Mexico. They had long ago adapted to a Tejano society, learning English and Spanish and bearing surnames such as Castro, de Leon, Flores, Solis, Gonzales, Villareal, Hernandez, Telles, and Leal, to name but a few.2 But the Lipan Apache people never assimilated. Inside their homes and within their families, one common admonition was passed down through the generations— "Never forget you are Lipan Apache."3

"Bullis's command next rode int Mexico on the trail of hostile Indians in September. On the 26th, three of the scouts reported that they had located a band of Lipans known to have engaged recently in raids into Texas. The Lipans had built village on Perdido Creek near Zaragoza. That same day, the scouts, together with detachments of the Eighth and Tenth Cavalry, crossed the Rio Grande. The force of ninety-one men under Bullis's overall command proceeded southwest for three days until it ame across the Lipan village. At sunrise, the troops harged the unsuspecting Indian and after a five-mie running fight, captured three women, two children, and about twenty horses and mules. They then destroyed the village and the Indians' entire supplies. The scouts' tactics once again had paid dividends, and the Lipans had suffered yet another defeat n their home territory." (p. 127)

Fear-Segal, J. (2007). White man’s club: Schools, race, and the struggle of Indian acculturation. Lincoln: Univ of Nebraska Press.

Gilfillan, M. (2018). Personal communication with Mark Gilfillan, District Tribal Liaison, US Army Corps of Engineers-Sacramento District. August 18, 2018.

Mulroy, K. (2003). Freedom on the border: The Seminole maroons in Florida, the Indian territory, Coahuila, and Texas. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press.

Opler, M. E. & Ray, V. F. (1975). The Lipan and Mescalero Apache in Texas. In An Ethnohistorical Analysis of Documents Relating to the Apaches in Texas. New York: Garland Publishing.

Ord, E.O.C. (1877). Ord to Adjutant General, Jul 11, RACC. Letters received by Office of Adjutant General, MP #M666, Roll 208, NA.

Turner, E. P. (1877). Turner to Secretary of War, Jan. 19, RACC, Letters received by Office of Adjutant General, MP #M666, Roll 204, NA.